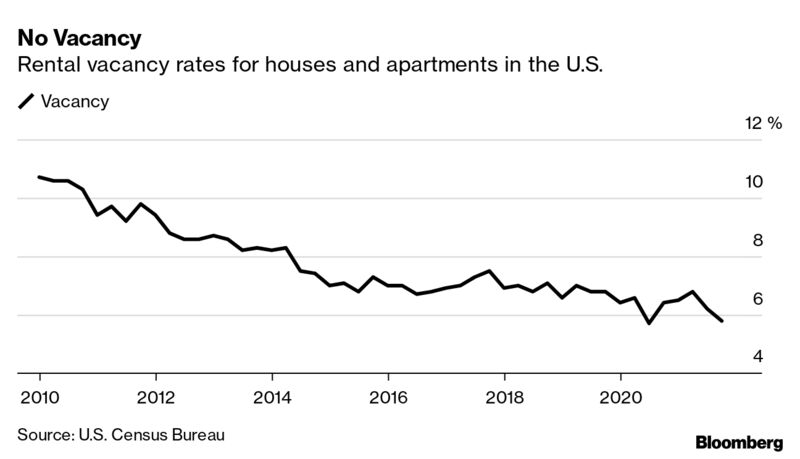

Apartment occupancy in the U.S. has hit an all-time high, meaning anyone looking for a new place is going to have a rough time of it.

Fully 97.5% of professionally managed apartment units are spoken for as of December, the highest figure on record, according to data from the property management software company RealPage. That’s more than 2 percentage points higher than the occupancy rate in December 2020, a difference that represents hundreds of thousands of households.

“I don’t think most people realize just how crazy that is,” says Jay Parsons, deputy chief economist for RealPage. “Not only is that a record, typically we consider 95 to 96% to be essentially full.”

But for most tenants, there may be a silver lining to the lack of options. Rents for available apartments have seen record increases over the last year, yet the occupancy rates suggest that most renters aren’t paying those prices.

High occupancy rates leave little margin for renters who need to relocate for jobs, education or other reasons. Winter is the shoulder season when it comes to these moves: Families typically settle in for the cold, the holidays, and the school year, then upend their lives over the summer. (The same seasonal pattern applies to forced exits through evictions.) In 2021, however, the occupancy rate rose steadily throughout the year, without the typical seasonal variation — another quirk of the pandemic.

Such low vacancy levels reflect a historically high number of renters renewing their leases. The lack of churn means that people hunting for new homes have fewer options. Apartments may be put on the market and leased before tenants leave the unit: “Clean, prep, paint, change the carpet, and get the next person in,” Parsons says.

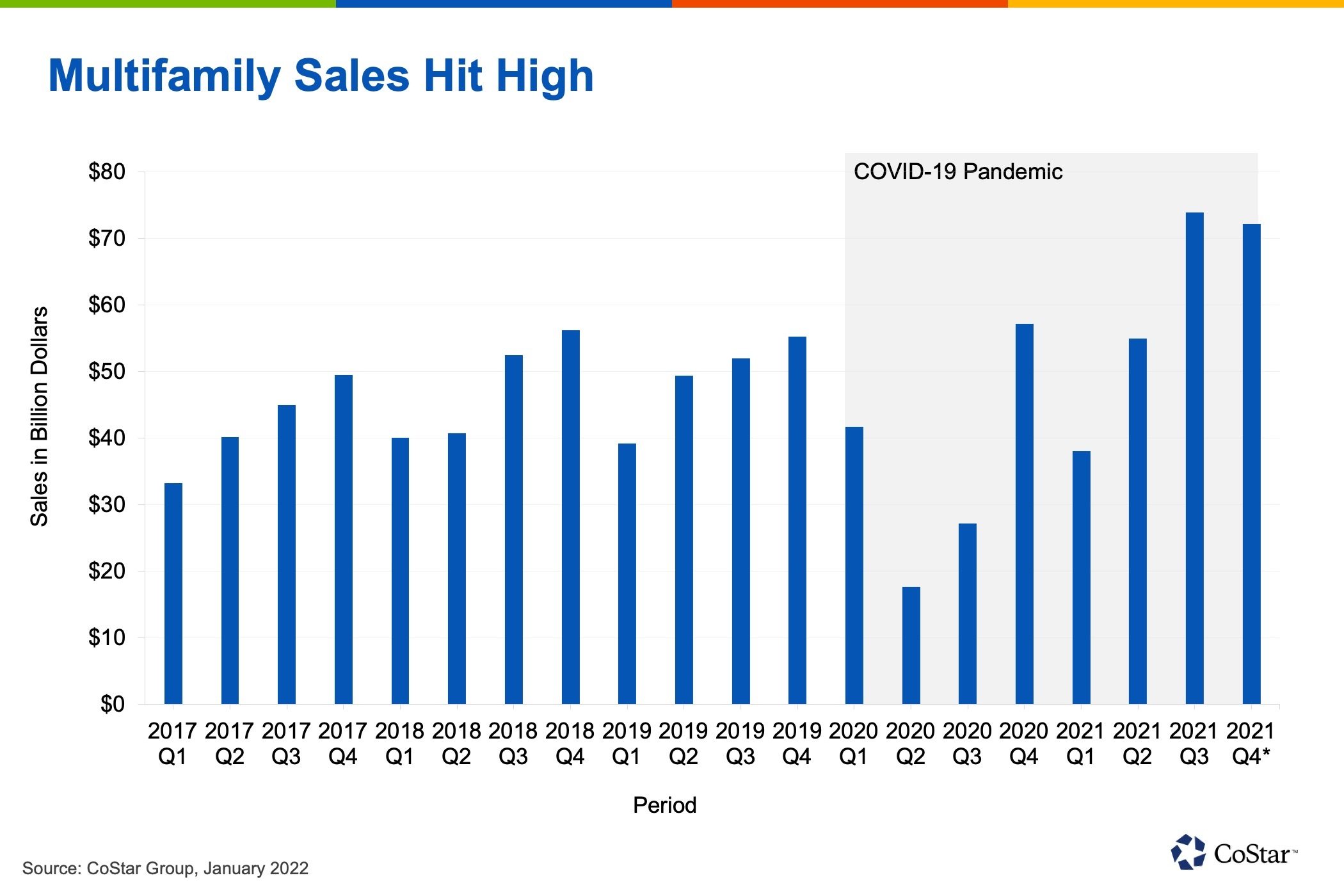

Abnormal is the pandemic normal, of course. Rents for market-rate apartments cratered during the first year of the pandemic as some residents decamped from cities (and, more importantly, new renters didn’t move in to replace them). Rents fell furthest in high-cost cities but also dipped in the suburbs of New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and a few other places. This plunge led building owners to offer huge discounts and concessions to try to lure renters — followed by steep double-digit rent hikes in 2021 as tenants finally returned to those buildings.

For tenants who already signed a lease or never left in the first place, spikes in rent listings might not affect them much. Landlords face a loss on paper when it comes to filling units, known in the industry as loss to lease. This is the difference between the advertised rent and what renters actually pay. An apartment building owner in Dallas might list a vacant unit at $200 higher than what the renter down the hall is paying. Property owners want to narrow this gap, and in a tight market, they have more leverage. Yet that same Dallas landlord marking up vacant units might not want to risk maxing out a current tenant’s rent when their lease comes due. It’s easier and more cost-efficient to keep them in place paying a less-than-maximum rent than to search for a new tenant. Very few apartment operators are going to move a household up to full price, Parsons says. Keeping a paying tenant in place is a high priority, especially after the chaos of the last two years.“When you send a renewal notice, 90 days out, there’s a lot of uncertainty. Especially in the Covid era, so much could change,” Parsons says. “There’s a real risk that we could have another economic challenge. There’s a balance of a higher chance of collecting revenue in an occupied unit versus a chance of zero revenue. Do you want to roll the dice?”

Rents are rising, and the discounts and concessions of 2020 are likely a thing of the past. Moreover, demand for housing continues to outpace the supply. In this specific moment, with omicron surging and rental chaos a recent memory, many landlords will stick with their current tenants. No matter: The housing shortage is so severe that property owners likely don’t need to charge max rents to make a bundle.

End Google Tag ManagerFamilies that do need to move right now face tough choices — or rather, fewer choices.