- CPI will remain close to 7% for a few months, Wells Fargo says

- Persistently high prices ramp up pressure on Fed, Biden to act

U.S. consumer prices are likely to extend their eye-popping gains after soaring last year by the most in nearly four decades, further burdening Americans and ramping up pressure on policymakers to act.

The consumer price index climbed 7% in 2021, the largest 12-month gain since June 1982, according to Labor Department data released Wednesday. The widely followed inflation gauge rose a faster-than-expected 0.5% over the month. Investors took a relatively sanguine view of the data, which were broadly in line with expectations.

Though many economists anticipate inflation to moderate to around 3% over the course of 2022, consumers are likely months away from a meaningful respite, especially as the omicron variant of the coronavirus worsens labor shortages and prevents goods from reaching store shelves.

If signs fail to materialize that inflation is moderating, Federal Reserve policymakers could be forced to embark on a steeper path of interest-rate hikes and balance-sheet shrinkage. It would also make it even tougher for President Joe Biden and Democrats to retain their congressional majorities in November’s midterm elections or pass their tax-and-spending package.

“The breadth of gains in recent months gives inflation inertia that will be difficult to break,” said Sarah House, senior economist at Wells Fargo & Co. “We expect the CPI to remain close to 7% the next few months.”

The report did offer some comfort to American families. Energy prices fell last month for the first time since April, and food prices -- while still rising -- moderated somewhat as the cost of meat fell. Biden said that reflected “progress” from his administration while acknowledging there’s more work to be done

Workers’ wages are simply not keeping up. Despite a slew of robust pay raises last year as businesses sought to fill a multitude of open positions, inflation-adjusted wages were down 2.4% in December from a year earlier.

Whether inflation falls as expected will depend on supply chains normalizing and energy prices leveling off. However, higher rents, robust wage growth, subsequent waves of Covid-19, and lingering supply constraints all pose upside risks to the inflation outlook.

While moderation is expected in some categories like vehicle prices and apparel, there’s “no particular reason to expect much of a cooling for the rest of the core,” Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont Securities LLC, said in a note.

“Sure, there will be goods categories that cool off once supply bottlenecks begin to ease later this year, but at the same time, the pressure from wages to prices is only going to ramp up,” Stanley said.

Omicron is poised to further disrupt already-fragile supply chains, due in part to quarantines and illness that have prevented many people from working. It’s also curbed demand for services like dining out. Bloomberg Economics’ daily gross domestic product tracker suggests activity was down sharply in the first week of 2022.

With omicron hitting the supply side of the economy through staffing, “inventory levels are likely to take even longer to normalize as a result, keeping upward pressure of goods prices through the year,” House said. That’s likely to be coupled with stronger services inflation, she said.

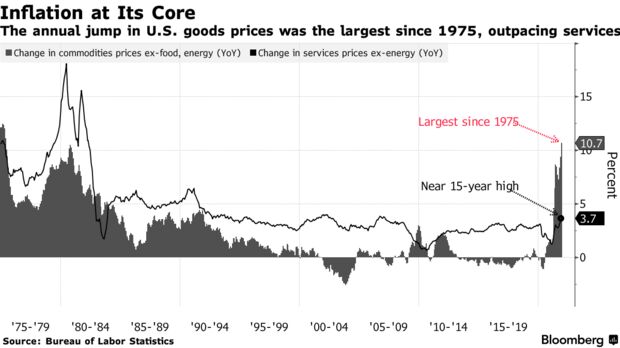

Last year, the increase in the CPI was largely due to high goods inflation. Excluding food and energy, the agency’s price index of goods surged 10.7% last year, the largest 12-month advance since 1975. Services costs climbed 3.7%.

But this year, economists expect service inflation to pick up steam as housing costs become a main driver of inflation.

Shelter costs, which were already one of the largest contributors to December’s gain, are expected to accelerate this year, offering an enduring tailwind to inflation. Other gauges of home prices and rents surged last year, but the full extent of those increases has yet to be reflected in the government’s measure.