The internal rate of return (IRR) is a widely used investment performance measure in finance, private equity, and commercial real estate. Yet, it’s also widely misunderstood.

What is Internal Rate of Return (IRR)?

The internal rate of return (IRR) is a financial metric used to measure an investment’s performance. The textbook definition of IRR is that it is the interest rate that causes the net present value to equal zero. Although the IRR is easy to calculate, many people find this textbook definition of IRR difficult to understand. Fortunately, there’s a more intuitive interpretation of IRR.

Simply stated, the internal rate of return (IRR) for an investment is the percentage rate earned on each dollar invested for each period it is invested.

We’ll walk through some examples of this more intuitive meaning of IRR step by step. But first, let’s take a closer look at the IRR formula.

IRR Formula

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) formula solves for the interest rate that sets the net present value equal to zero.

The IRR formula can be difficult to understand because you first have to understand the Net Present Value (NPV). Since the IRR is an interest rate that sets NPV equal to zero, what is NPV, and what does it mean to set the NPV equal to zero?

Simply stated, the Net Present Value (NPV) is the present value of all cash inflows (Benefits) minus the present value of all cash outflows (Costs). In other words, NPV measures the present value of the benefits minus the present value of the costs:

So, another way to think about the IRR formula is that it is calculating the interest rate that makes the present value of all positive cash flows equal to the present value of all negative cash flows. When this happens, then the net present value will equal zero:

This is what it means to set the net present value equal to zero. If we want to solve for IRR, then we have to find an interest rate that makes the present value of the positive cash flows equal to the present value of the negative cash flows.

Next, let’s walk through how to calculate IRR in more detail, and then we’ll look at some examples.

How to Calculate IRR

In most cases, the IRR is calculated by trial and error. This is accomplished iteratively by guessing different interest rates to use in the IRR formula until one is found that causes the net present value to equal zero.

A guess is used for the interest rate variable in the IRR formula, and then each cash flow is discounted back to the present time using this guess as the interest rate (often called the discount rate). This process repeats until a discount rate is found that sets the net present value equation equal to zero.

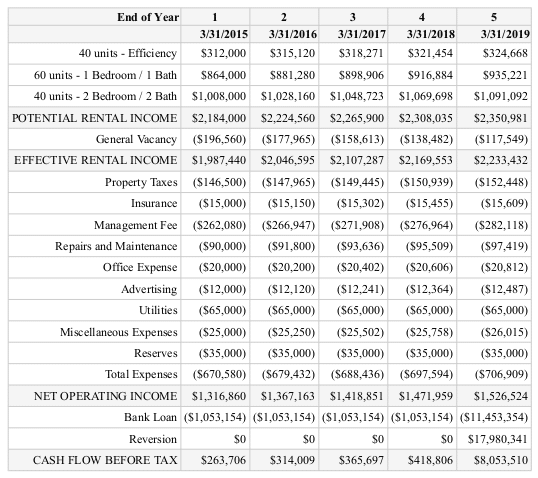

In the example above, the present cost is $100,000 as shown in Time 0. This is shown as a negative number when dealing with the time value of money because it is a cash outflow or cost. Each future cash inflow is shown on the vertical timeline as a positive number starting in Time 1 and ending in Time 5.

The IRR calculation repeatedly guesses the interest rate that will make the sum of all present values equal to zero. When this happens, the present value will equal the present cost, which will set the net present value equal to zero.

As you can imagine, guessing different interest rates over and over is a tedious and time-consuming process, so it is hard to calculate IRR by hand. However, the IRR calculation can be easily performed using a financial calculator or the IRR function in Excel.

How to Calculate IRR in Excel

The internal rate of return can be calculated using the IRR function in Excel:

To calculate IRR in Excel, you need:

- A set of evenly spaced cash flows. This is C2:C7 in the IRR Excel example above.

- At least one positive and one negative number in your set of cash flows. In the example above, the negative cash outflow occurs in year 0 and years 1-5 contain positive cash inflows.

- An optional guess to help the IRR formula in Excel. A guess is usually not necessary when calculating IRR in Excel. If the guess is omitted, then by default, Excel will use 10% as the initial guess. If the IRR can’t be found with up to 20 guesses, then Excel will return an error. In this case, a reasonable guess can be provided to the IRR function in Excel. For example, if you have monthly or weekly cash flows, then you may need to use a guess that is much smaller than the default 10%.

The reason Excel requires evenly spaced cash flows is that IRR calculates a periodic interest rate. To calculate a periodic rate, cash flows must occur regularly over the same period of time. For example, an annual IRR will require cash flows that occur annually and a monthly IRR will require cash flows that occur monthly.

The XIRR function in Excel is commonly used to calculate a return on a set of irregularly spaced cash flows. Instead of solving for an effective periodic rate like the IRR, the XIRR calculates an effective annual rate that sets the net present value equal to zero.

IRR Meaning

Memorizing IRR formulas and calculations is one thing, but truly understanding what IRR means will give you a big advantage. Let’s walk through a detailed example of IRR and show you exactly what it does, step-by-step.

Suppose we are faced with the following series of cash flows:

This is pretty straightforward. An investment of $100,000 made today will be worth $161,051 in 5 years. As shown, the IRR calculated is 10%. Now let’s take a look under the hood to see exactly what’s happening to our investment in each of the 5 years:

As shown above in year 1 the total amount we have invested is $100,000 and there is no cash flow received. Since the 10% IRR in year 1 we receive is not paid out to us as an interim cash flow, it is instead added to our outstanding investment amount for year 2. That means in year 2 we no longer have $100,000 invested, but rather we have $100,000 + 10,000, or $110,000 invested.

Now in year 2 this $110,000 earns 10%, which equals $11,000. Again, nothing is paid out in interim cash flows, so our $11,000 return is added to our outstanding internal investment amount for year 3. This process of increasing the outstanding “internal” investment amount continues all the way through the end of year 5 when we receive our lump sum return of $161,051. Notice how this lump sum payment includes both the return of our original $100,000 investment, plus the 10% return “on” our investment.

This is much more intuitive than the common mathematical explanation of IRR as “the discount rate that makes the net present value equal to zero.” While technically correct, it doesn’t help us all that much in understanding what IRR actually means. As shown above, the IRR is clearly the percentage rate earned on each dollar invested for each period it is invested. Once you break it out into its individual components and step through it period by period, this becomes easy to see.

IRR vs CAGR

IRR can be a helpful decision indicator for selecting an investment. However, there is one critical point that must be made about IRR: it doesn’t always equal the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) on an initial investment.

Let’s take an example to illustrate. Suppose we have the following series of cash flows that also generates a 10% IRR:

In this example, an investment of $100,000 is made today and in exchange we receive $15,000 every year for 5 years, plus we also sell the asset at the end of year 5 for $69,475. The calculated IRR of 10% is the same as our first example above. But let’s examine what’s happening under the hood to see why these are two very different investments:

As shown above in year 1 our outstanding investment amount is $100,000, which earns a return on investment of 10% or $10,000. However, our total interim cash flow in year 1 is $15,000, which is $5,000 greater than our $10,000 return “on” investment. That means in year 1 we get our $10,000 return on investment, plus we also get $5,000 of our original initial investment back.

Now, notice what happens to our outstanding internal investment in year 2. It decreases by $5,000 since that is the amount of capital we recovered with the year 1 cash flow (the amount exceeding the return on portion). This process of decreasing the outstanding “internal” investment amount continues all the way through the end of year 5. Again, the reason our outstanding initial investment decreases is that we are receiving more cash flow each year than is needed to earn the IRR for that year. This extra cash flow results in capital recovery, thus reducing the outstanding amount of capital we have remaining in the investment.

Why does this matter? Let’s take another look at the total cash flow columns in each of the above two charts. Notice that in our first example the total cash flow was $161,051 while in the second chart the total cash flow was only $144,475. But wait a minute, I thought both of these investments had a 10% IRR?! Well, indeed they did both earn a 10% IRR, as we can see by revisiting the intuitive definition of IRR:

The Internal rate of return (IRR) for an investment is the percentage rate earned on each dollar invested for each period it is invested.

The internal rate of return measures the return on the outstanding “internal” investment amount remaining in an investment for each period it is invested. The outstanding internal investment, as demonstrated above, can increase or decrease over the holding period. IRR says nothing about what happens to capital taken out of the investment. And contrary to popular belief, the IRR does not always measure the return on your initial investment.

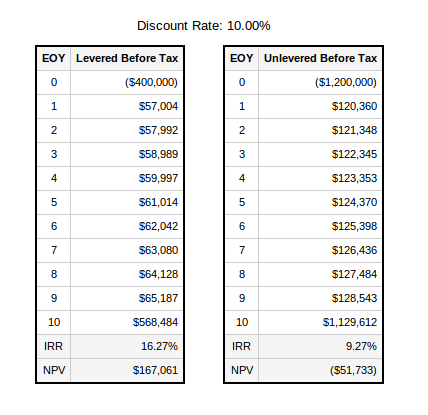

What is a good IRR?

A good IRR is one that is higher than the minimum acceptable rate of return. In other words, if your minimum acceptable rate of return, also called a discount rate or hurdle rate, is 10% but the IRR for a project is only 8%, then this is not a good IRR. On the other hand, if the IRR for a project is 18%, then this is a good IRR relative to your minimum acceptable rate of return.

Individual investors usually think about their minimum acceptable rate of return, or discount rate, in terms of their opportunity cost of capital. The opportunity cost of capital is what an investor could earn in the marketplace on an investment of similar size and risk. Corporate investors usually calculate a minimum acceptable rate of return based on the weighted average cost of capital.

Before determining whether an investment is worth pursing, even if it has a good IRR, it is important to be aware of some IRR limitations.

IRR Limitations

IRR can be useful as an initial screening tool, but it does have some limitations and shouldn’t be used in isolation. When comparing two or more investment alternatives, the IRR can be especially problematic. Let’s review some disadvantages of IRR you should be aware of.

IRR and timing of cash flows

The internal rate of return for an investment only measures the return in each period on the unrecovered investment balance, which can vary over time. That means the timing of the cash flows can impact the profitability of an investment, but this won’t always be indicated by the IRR. Recall the two IRR examples discussed above:

The first investment on the left produces cash flow each year, while the second does not. Although both investments produce a 10% IRR, one is clearly more profitable than the other. The reason is that in the first investment, the unrecovered investment balance changes from year to year, while in the second investment it does not.

As a result, the IRR could conflict with other measures of investment performance, such as the equity multiple or net present value. This is one reason why the IRR can be useful as an initial screening tool, but shouldn’t be used in isolation.

IRR ignores the size of the project

The IRR also does not account for the magnitude of a project. That means the project with the highest IRR won’t necessarily be the project with the highest profit. For example, consider the following two options.

- Option 1: Invest 100 at time 0 and get back 200 at time 1. This results in a 100% IRR, and a gross profit of 200-100 or 100.

- Option 2: Invest 1,000,000 at time 0 and get back 1,100,000 at time 1. This results in a 10% IRR, and a gross profit of 1,100,000 – 1,000,000, or 100,000.

Even though option 1 has a higher internal rate of return, option 2 has the highest profit. This can happen because IRR ignores the size of the project.

Multiple IRRs

When a stream of cash flows has more than one sign change, then multiple IRRs can exist. For example, consider the following scenario:

When you calculate an IRR on these cash flows, you actually get multiple solutions! The reason this occurs has to do with Descartes’ rule of signs concerning the number of roots in a polynomial. This means that the number of positive IRRs can be as many as the number of sign changes in the cash flows.

The Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR) was designed to solve the multiple IRR problem and many other limitations of IRR as well.

IRR Reinvestment Assumption Myth

One of the most commonly cited limitations of the IRR is the so-called “reinvestment assumption.” In short, the reinvestment assumption says that the IRR assumes interim cash flows are reinvested at the same rate as the IRR.

The idea that the IRR assumes interim cash flows are reinvested is a major misconception that’s unfortunately still taught by many business school professors today.

As shown in the step-by-step approach above, the IRR makes no such assumption. The internal rate of return is a discounting calculation and makes no assumptions about what to do with periodic cash flows received along the way. It can’t because it’s a DISCOUNTING function, which moves money backwards in time, not forward.

Should you consider the yield you can earn on interim cash flows that you reinvest? Absolutely, and there have been various measures introduced over the years to turn the IRR into a measure of return on the initial investment, such as the Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR).

This is not to imply that the IRR doesn’t have some limitations, as we discussed in the examples above. It’s just to say that the “reinvestment assumption” is not among them.

Conclusion

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a popular measure of investment performance. While it’s normally explained using its mathematical definition (the discount rate that causes the net present value to equal zero), this article showed step-by-step what the IRR actually does. What is IRR? Once you walk through the examples above, this question becomes much easier to answer. It also becomes clear that the IRR isn’t always what people think it is. That is, IRR isn’t always the compound annual growth rate on the initial investment amount. IRR can be useful as an initial screening tool, but it does have several limitations and therefore should not be used in isolation.

Source: Internal Rate of Return (IRR): What You Should Know

https://www.creconsult.net/market-trends/internal-rate-of-return-irr-what-you-should-know/